Ideas for Using Images

When students skim a document, images can quickly convey information and increase students’ understanding of standard components of the syllabus. Here are some ideas for adding images to your syllabus:

-

Include a visual representation of the grade distribution list, such as a pie chart.

-

Use images of key authors, required textbooks, or course management system logos such as Canvas or Blackboard.

-

Incorporate images to depict main concepts for class alongside a course description.

-

Create word clouds for lists of key terms.

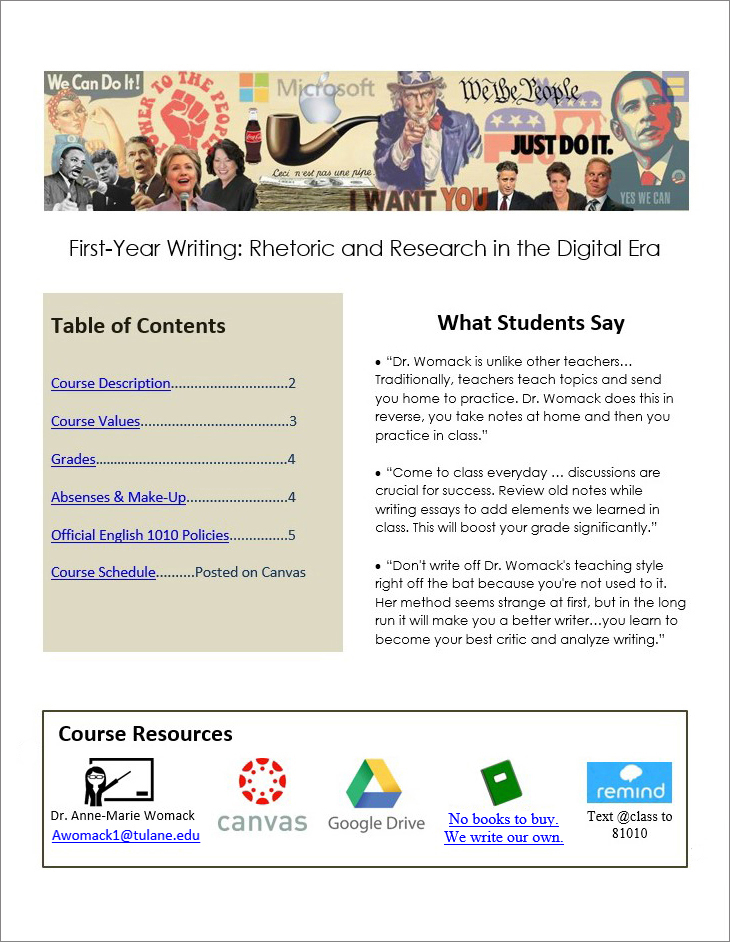

The following before and after images illustrate one instructor’s move from a traditional text based syllabus to a more accessible image driven syllabus.

The syllabus on the left shows dense text and undersized margins. The page contains the course information, required texts, course description, and grade distribution. There are bulleted lists, but the text covers almost every inch of the page.

In the newer version, the information is organized in discernible chunks. At the top, a course banner contains a collage hinting at the rhetoric the course covers: famous politicians, including Martin Luther King Jr. and Hillary Clinton; American slogans from “Power to the People” to “Just do It;” and iconic images from Uncle Sam to the Microsoft logo. Beneath the banner reads the course title, First Year Writing: Rhetoric and Research in the Digital Era.

Below on the left, a table of contents offers hyperlinks to the syllabus components, such as course description, grades, and official policies. On the right, three student quotes about the course provide a quick idea of the class structure. Blocked together at the bottom, hyperlinked images show essential course resources: a teacher icon with the instructor’s name and email address, a Canvas learning management system icon, a Google Drive icon, a notebook icon that takes students to a prompt to create their own textbook, and the Remind logo for a class text message system. The new version strives to provide redundancy across modes: images for visual learners; alt text for auditory learners; and digestible sections for learners with reading disabilities.

Text Only Syllabus

What is not visible on the syllabus image above is a hidden hyperlink in a font color matching the background. At the top of the page, it reads “Text only version of syllabus” and hyperlinks to a version more legible to screen readers.

Many of the features that improved visual design here (such as text boxes) created difficulties for the Microsoft narrator we used to test the page. Narrator is described more in Microsoft’s Accessibility Guide for Educators. That doesn’t mean though that images or organizational tools such as bullet points do not convey useful information to people relying on text. The text-only syllabus still includes alternative text for images, but instead of embedding it in an image, it lists it in the main text and doesn’t include the image.

Alternative Text for Images (Alt Text)

Images are not automatically accessible to screen readers on a computer. Writers must build image descriptions into the code of a document or integrate image descriptions into the full text as demonstrated in earlier examples. This alternative text (alt text) allows images to be read by screen readers. Bryan Gould of the National Center for Accessible Media poses three questions to consider when creating alt text:

- Why is the image there?

- Who is the intended audience?

- If there is no description what will the readers miss?

This third question, Gould points out, does not imply that alt text should include every visual detail, but rather that it should include the most important concepts.

What constitutes the most important concepts changes based on the context, so authors should consider the rhetorical situation when crafting alt text. STEM guidelines, for example, suggest that alt text be brief and focused on data, not extraneous visual details. In an English class where students will analyze the image, though, more description would be necessary. The following are general guidelines to consider when creating alt text:

-

Don’t enter “photograph” or “picture of.” Screen readers already note the presence of an image.

-

Move from general description to specifics to allow readers to choose whether to go further and deeper in the same way a visual reader does.

-

Keep text as concise as possible based on the rhetorical situation. Many online sources recommend between 5-15 words, but this number is not an absolute. All of the alt text examples below use over 20 words to make room for crucial historical details.

-

Ask someone who has not seen the image to review the alt text.

Alternative Text from National News Outlets

The alt text examples in this section come from national news sources. The descriptions demonstrate how important it is to know the context of the image as well as the people, events, and objects it depicts.

An American sailor kisses a nurse among the crowd in Times Square celebrating VJ Day, the long-awaited victory over Japan in WWII, on August 14, 1945.Wired Magazine

President Barack Obama walks across the tarmac as he prepares to board Air Force One before his departure from Andrews Air Force Base, Md., Oct. 9, 2015.Time Magazine

Using hydrotechnics and mist-based holographic projections, a 40-foot hologram of Carmelo Anthony was created in the Hudson River.CNN.

Alternative Text from Alt Text Bots

Some alt text bots online can help with crafting alt text. The images below demonstrate both the strengths and drawbacks of bots. (These were created using the now defunct alttextbot.com.) The first image is the same famous VJ day kiss image cited above, but the bot describes just a couple kissing. The Times lengthier description gave more necessary context so readers could understand the photo within its historical moment.

couple kissing at grayscale

The second image below seems busy and complex, which could present challenges when creating alt text. It features a silhouette of a head being encircled by 50 small objects including a computer, arrow, house, and star. In the middle of the circle is the word kNOWledge. The bot, though, does a good job of boiling it down to its essential meaning, a depiction of knowledge.

knowledge illustration with silhouette of person

Null Alternative Text

If alt text is ever left blank, a screen reader will notify the student that an image is present but has no description. This omission excludes readers from the document.

Sometimes with purely decorative images, though, like a flourished line between text sections, as shown below, alternative text may seem unnecessary.

By creating null alt text instead, the screen reader will know to skip over the nonessential image entirely. Instead of leaving alt text blank, here are tips for using null alt text:

-

To create null alt text, include two quotation marks in the alt text box: “”

-

Don’t use null alt text if the image is the only thing identifying a link, otherwise a user will not be able to navigate to the link.

-

If an image is described in a caption, use “refer to caption” as alt text instead of null.

Color Universal Design

Images often introduce color, a format not legible to all readers. Kei Ito and Masataka Okabe provide helpful guidelines for universal color design online, in which they discuss common types of color blindness that affect red, green, and blue color perception. Like all disabilities, colorblindness affects individuals uniquely, but the following guidelines can help make colors more accessible.

-

Information should never be conveyed through color alone.

-

Create contrast not only in color hue, but in brightness.

-

Avoid layering black on dark red, which can appear as black on black.

-

If you use laser pointers in class, choose green, which is more widely accessible according to Masataka and Ito.

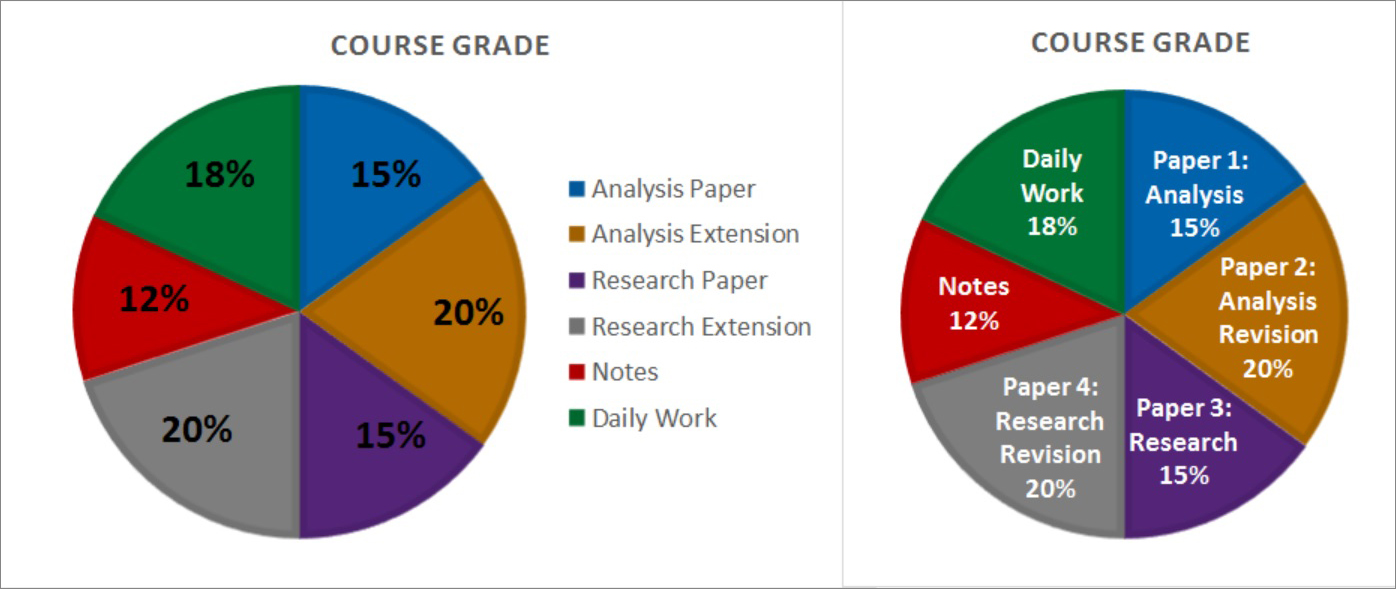

Consider the two contrasting images as an example of applying the principles of universal color design.

Both visuals present assignments and their grade worth in pie chart form. Each uses differently color coded pie slices. But on the left, the less accessible pie chart lists a separate color coded key to the side that designates which slice goes with which assignment. It layers black text on dark chart colors.

In contrast, the sample on the right labels the assignments within the slices and uses white text on dark background colors. Moreover, each slice is outlined by a darker version of the hue–the blue slice is outlined by a dark blue line, for example. So contrast, not simply color divides the sections, which can prevent them from blurring together. Image-driven syllabi, when accessible in multiple modes, can create an engaging tone for the course.